Bolivia became the world’s top importer of mercury since 2019, according to the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), which tracks global trade flows. The reason for that sits behind the booming small-scale artisanal gold mining industry, associated with the global gold price rise in recent years. The use of mercury in gold mining has severe impacts on environmental protection, deforestation and especially on the rights and livelihoods of indigenous peoples since it contaminates waters used for drinking, washing and fishing.

Likewise, mining is destroying Alto Nangaritza, one of the last well-preserved forest links between the Andes and Ecuadorian Amazon. The construction of roads connecting remote Indigenous communities to the broader provincial network facilitated the miners’ movement and some indigenous people also started to extract gold to increase their income.

Encroaching on indigenous lands has also happened in the Amazon in Peru, Venezuela and Brazil, with miners increasingly emboldened.

Regulations and enforcing them

The Amazon is home to many indigenous tribal communities and hosts several world heritage sites. When it is licenced and controlled, artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) can offer job opportunities and help fight poverty.

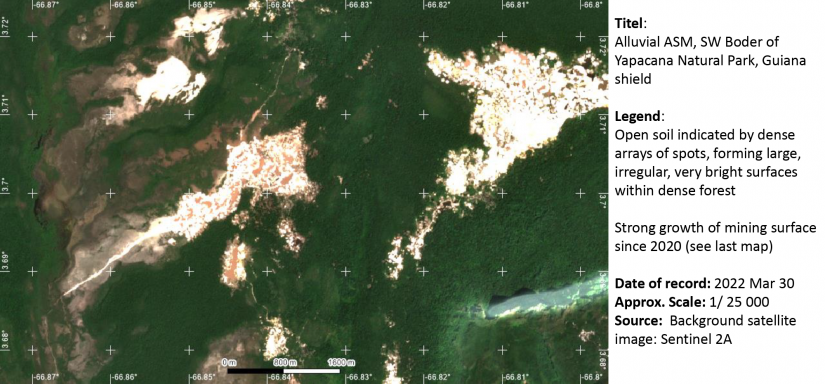

However, monitoring environmental damage and mining is challenging and rare due to the high level of violence and conflict in several regions, preventing authorities and environmental watchdogs from entering the areas. As a consequence, uncontrolled and harmful ASM proliferates.

Remote sensing earns a chance to become an excellent tool for collecting evidence and improving visibility.

A free and easy access platform to trigger alarms

In the context of a Permanently Open Call project, GAF has developed and implemented an easy-to-use web-based system to recognise indications of unlicensed artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) in tropical forests – the ASM Alert platform.

The platform combines free and publicly available satellite data – in particular, European Copernicus Sentinel imagery – with other geodata layers and machine learning for the analysis.

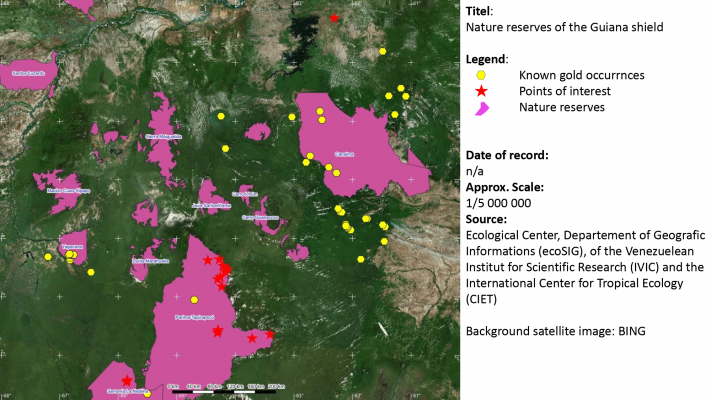

The probability of ASM is calculated based on combined EO-derived indicators, such as forest degradation, vicinity to the water network and vicinity to high gold potential (derived from existing geologic data). The spatial association of all 3 indicators is a very good first proxy to detect ASM. Once the potential sites of gold mining are localised, the next step is to compare them with the background information available. This might be VHR satellite data, or ground data from external sources or any other source of information. The platform then enables the ordering of commercial, very-high-resolution (VHR) satellite imagery for the identified target areas.

The web-based system offers easy and open access to facilitate and accelerate action after the detection of illegal ASM. The current version has been demonstrated and validated in the tropical forests of the Guiana Shield in Venezuela, which are part of the largest mega biodiversity area in the Amazon.

Evidence collection for future enforcement?

The project addresses stakeholders on all levels – from local communities to international organisations.

The latter range from the OECD, to the Minamata Convention (an international treaty designed to protect human health and the environment from anthropogenic emissions and releases of mercury and mercury compounds), the Organisation of the American States, the World Bank, the United Nations Environment Program, the World Heritage Convention and also the International Criminal Court.

Any law to be enforced needs evidence for its application.

Venezuela, where the ASM Alert platform is being demonstrated, is being referred to the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity. While material ecocide is not yet formally recognised by the ICC, direct evidence for ecocide is being gathered by a few scientists who can test soil and water samples to ascertain mercury’s concentration in the mined rivers and forests. However, this is dangerous and probably not sufficient.

EO-derived information may provide in this and similar cases valuable data and evidence.

Featured image: Auyantepuy – Salto Angel in the Cañon del Diablo. Photo by Charles Brewer Carias, courtesy of SOS Orinoco