The pandemic has been and is still striking hard on cultural heritage: collapse in tourism revenues (according to UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee, as of early April last year, 71% of the 1,121 World Heritage sites had been closed and 18% were only partially open), increased vulnerability to looting, suspension of rehabilitation, conservation and archaeological exploration works.

On top of that, there is a decline in cultural funding from governments and philanthropists, moving towards healthcare and environment.

What appears to be a plunge into disaster might turn into an opportunity: organisations are rethinking their models for protecting heritage sites in the future.

Can Earth Observation play a role in this context?

A number of studies have demonstrated a number of potential uses of data from satellites when looking at cultural heritage. The range of possibilities is wide, starting with new archaeological discoveries and reaching up to safeguarding.

Satellites clearly offer the great advantage of allowing non-invasive investigation of remote, inaccessible (due to natural constraints or political reasons) areas, which is often the case for sites of historical interest.

Since the 1980s, the use of SAR data has been explored to identify buried archaeological features in dry, desert areas thanks to its all-weather functioning, ground penetration and target dielectric properties intelligence. Multi-frequency, multi-temporal, multi-incidence and polarimetric capabilities of radar are still at a very early stage of exploitation though.

Historical aerial and satellite imagery (such as the Corona Cold War-era satellite imaging program data, now declassified) are interesting resources for archaeological discovery and mapping, primarily because they offer a perspective on the landscape that predates widespread land use changes, such as urban expansion, industrialization of agriculture, construction of reservoirs, seen in recent decades.

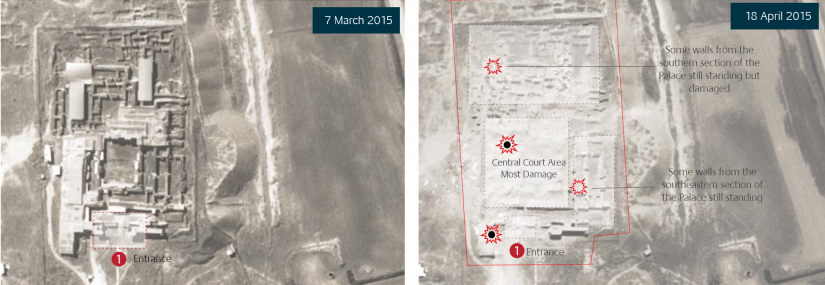

Only the combination of a historical data archive with very high resolution optical data has made observation of destruction and damages to cultural heritage locations caused by conflicts in areas like Iraq, Syria and Yemen possible.

The Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research (ATHAR) project has reported a rise in antiquities trafficking on Facebook during 2020: looting (illegal excavations in archaeological heritage sites) has dramatically increased as a consequence of economic crisis and reduced surveillance related to the pandemic. To this purpose very high resolution (VHR) optical imagery, mainly black-and-white panchromatic, or pan-sharpened multispectral has been mostly used to date, with limited SAR exploitation. Yet the full potential of optical has to be unveiled when it comes to testing the use of spectral indices.

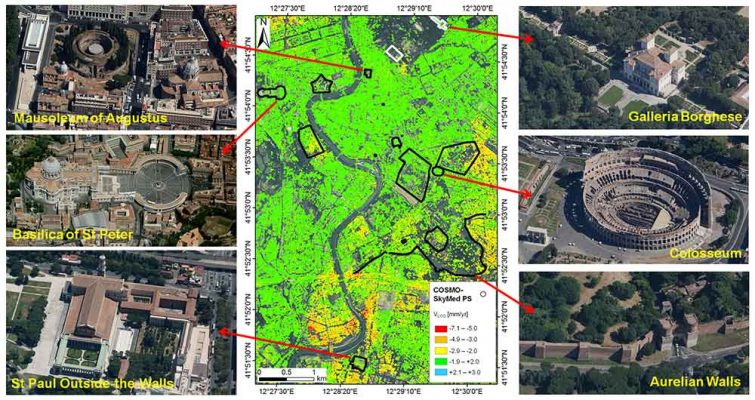

But hazards for cultural heritage are manifold. PROTHEGO (PROTection of European Cultural HEritage from GeO-hazards) is a project applying radar interferometry (InSAR) to monitor monuments and sites in Europe which are inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List and are potentially unstable due to geohazards.

Extreme events, expected climate change consequences, rapid urban or tourist development add to the list of hazards that may cause risks to cultural heritage sites where EO monitoring can certainly provide useful information.

Finally, a role for EO in cultural heritage can also be played in more unexpected ways, not via the data themselves but rather via their technical features. FITS (Flexible Image Transport System) format, the one selected for long term EO data preservation, has been applied to the Vatican Library ancient documents in order to make them more accessible while guaranteeing their conservation.

Which future to preserve our past?

To date, remote sensing techniques have been applied somewhat narrowly to mostly site-based research in cultural heritage sites.

Nonetheless, big data analysis techniques exploiting AI, advanced data fusion, open data policies and collaborative platforms are currently modifying the picture and offering new perspectives to archaeologists and cultural heritage stakeholders.

The Geospatial Platform for Andean Culture, History and Archaeology (GeoPACHA) is an open source, browser-based platform that lets users discover and document archaeological sites in the Andes by systematically surveying satellite and historic aerial imagery via networks of trained teams. The comprehensive basemap of the colonial towns (reducciones) built during the mass Inca Empire resettlement in the 1570s by Spanish conquerors helped spotting the distribution pattern of settlements, and showing to what extent Spanish governance was reimagined in an Inca model.

Machine learning-based classification of multisensor, multitemporal satellite data expands the known concentration of Indus settlements in the Cholistan Desert in Pakistan (ca. 3300 to 1500 BC), with the detection of hundreds of new sites deeper in the desert than previously suspected. These distribution patterns have major implications regarding the influence of climate change and desertification in the collapse of the largest of the Old-World Bronze Age civilizations.

A wealth of new EO data (including new high-resolution SAR in different bands, such as P-band Iceye or X-band Paz) are also ready to be explored.

Actions to explore the largely untapped potential of EO for cultural heritage are encouraged by ESA and will find support in the new Open Call for proposals, in use of free Copernicus Sentinels as well as TPM data and further sponsorship from the Network of Resources.

Featured image : Boats in World Heritage Venice lagoon pre and during Covid-19 lockdown. A large part of the traffic is tourism related. Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (19 April 2019 – 13 April 2020)